Robert William Pugh 1839-1887

Family background

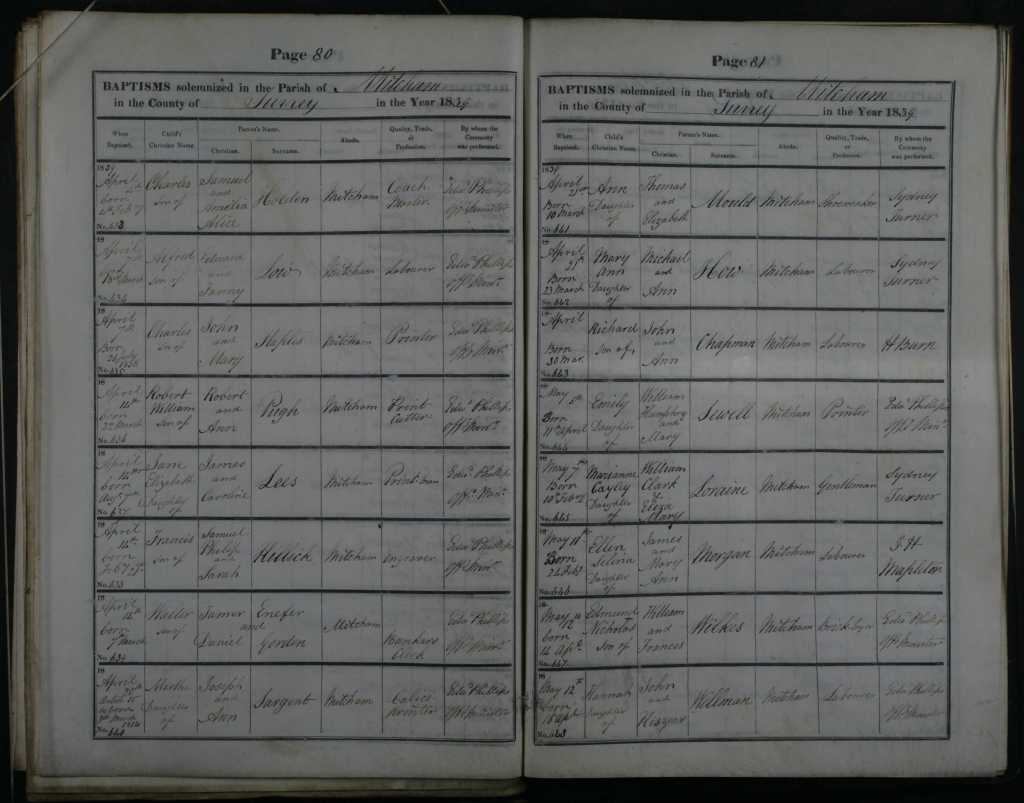

Robert was born in Mitcham Surrey, now in the London Borough of Merton, on 22nd March 1839, the fourth child of Robert Pugh, a print cutter, and Ann Perry. He was baptised at St Peter & St Paul church in Mitcham by Edward Phillips on 14th April 1839.

The 1851 census shows him living with his parents at 88 Phips (now Phipps) Bridge Road in Merton, and working as an Errand Boy.

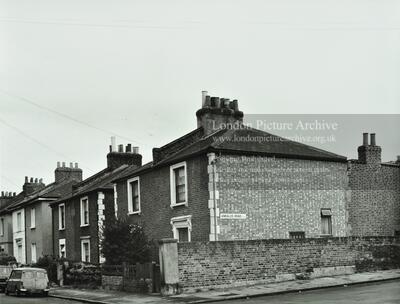

Today, the house looks like this. It’s now part of a conservation area, and according to this document, was built between 1800 and 1849 (see page 5).

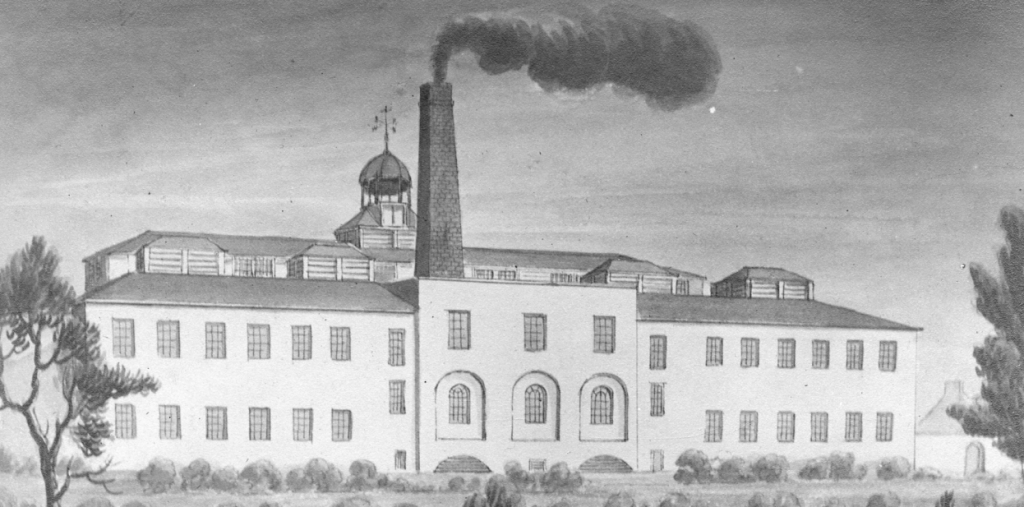

Robert may have seen this Patent Steam Laundry at Phipps Bridge, two minutes from his home, which was auctioned in 1827.

Events in Robert’s childhood

Britain and its empire were rapidly changing during Robert’s childhood. From his birth until he joined the Rifle Brigade in 1858 the population of the country increased by 25%, and would almost double in his lifetime. Slavery was only abolished in the British Empire the year before he was born. The Chartist movement was active from 1838-57, throughout his childhood.

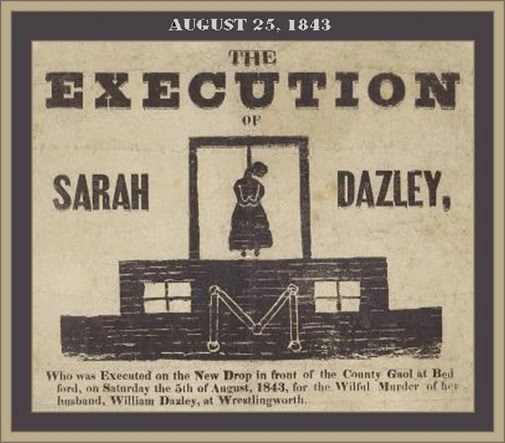

In the year of his birth, the first Rebecca riots took place in Wales, Hong Kong was seized as a base by the British in preparation for the First Opium War, and the First Afghan War started. Both of these wars would impact on his military career. In 1840 the Uniform Penny Post was introduced, the foundations of Nelson’s column were laid, New Zealand’s founding document, the Treaty of Waitangi was signed and the Act of Union created the Province of Canada. In 1843 the SS Great Britain, by far the largest vessel afloat at the time, was launched in Bristol, and Sarah Dazley, the last woman to be publicly executed in Britain was hung outside Bedford Prison.

The Irish potato famine started in 1845, when he was six, and by the time he was 16 2 million Irish people had emigrated to America and Australia and 750 thousand had come to Britain; the population only returned to pre-famine levels in 2016. When it ended in 1852 a quarter of the populations of Liverpool and east coast American cities were Irish. When he was seven, the first operation under anaesthetic in Britain took place, the Koh-i-Noor diamond was surrendered to Queen Victoria, the planet Neptune was seen for the first time and most restrictions on Jews, Roman Catholics and Dissenters in public life were removed by the Religious Opinions Relief Bill. The following year the Vegetarian Society was founded and the so-called Ten Hour Act restricted the working day to ten hours for women and boys aged 13-18. In 1848 Waterloo station opened, and across London the first WH Smith bookstall opened at Euston station. In 1849 the Second Anglo-Sikh war ended and the Punjab was annexed by the British. Back in the UK, Karl Marx moved to London and what would become the House of Fraser opened its first store Glasgow. In 1850 Anglesey was connected to the civilised world by Robert Stephenson’s Britannia Tubular Bridge.

courtesy of the RCAHMW and its Coflein website.

The Great Exhibition in Hyde Park opened when Robert was twelve, and is said to have been visited by six million people, one third of the population at the time. In 1852, Kings Cross station, the largest in Europe, opened, and the first public library offering free lending opened in Campfield Manchester. The Crimean War was fought in Robert’s teenage years, from 1853-6. A cholera outbreak in London in 1854 killed ten thousand people, but was traced to a single water pump by Dr John Snow, proving that it was water-born. In 1856 the Second Opium War broke out, and Glan Rhondda was composed in Pontypridd. Just before Robert moved to the Rifle Brigade, in April 1857 Lord Palmerston was elected Whig Prime Minister, but resigned after a counter-terrorism bill was rejected and was replaced by the Earl of Derby, a Tory. Charles Dickens published Little Dorrit, the SS Great Eastern was launched, France and the UK formally declared war on China in the Second Opium War, and the Royal Opera House opened.

What was happening in India, and what might Robert have known?

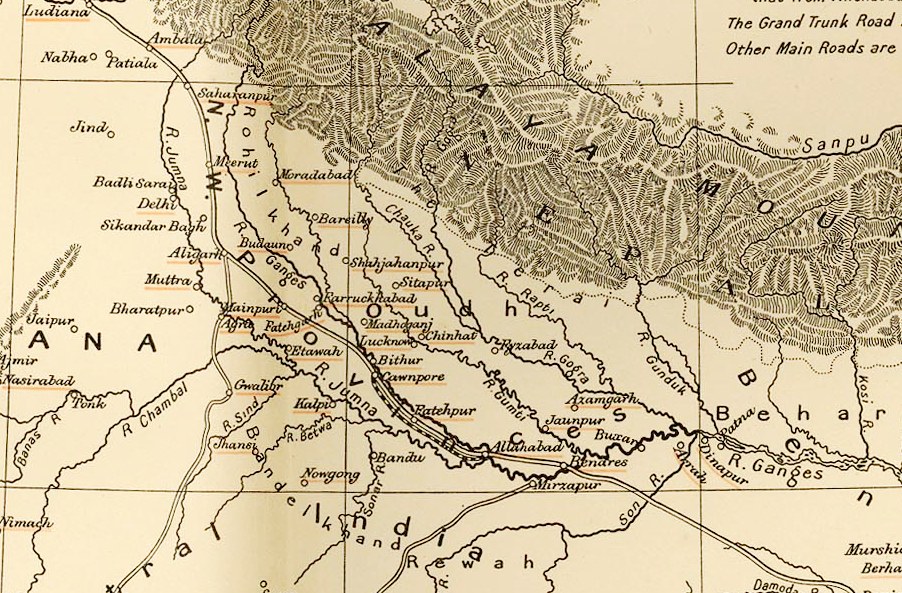

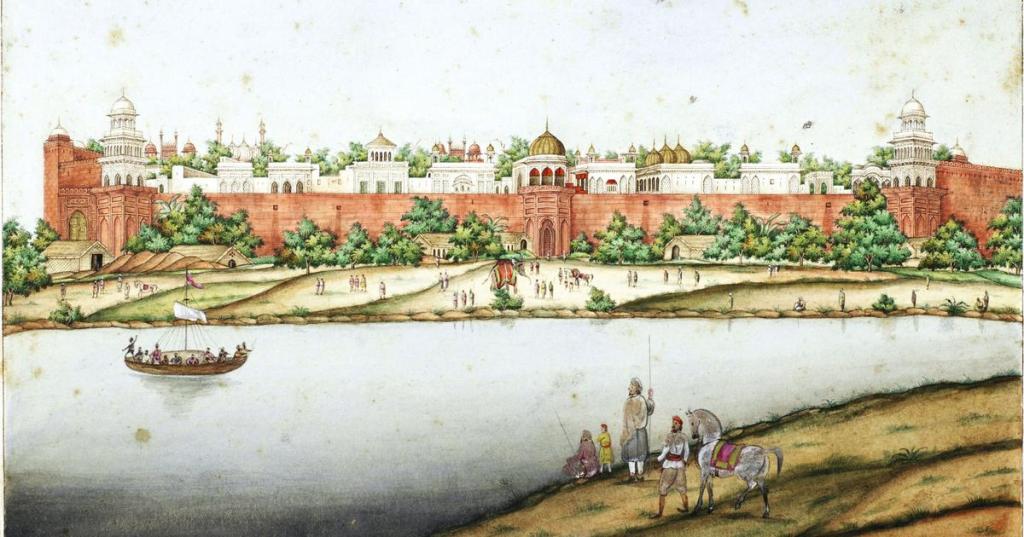

Robert was initially stationed in Awadh (also spelt Oudh), which is now the north eastern part of the state of Uttar Pradesh. It is to the east of Delhi where the Mughal Emperor still lived in the Red Fort. With the decline of the the central Mughal state, governance of Awadh was under the semi-autonomous Nawabs, whose capital was Lucknow. After the 1801 Treaty of Lucknow, Awadh had essentially become a client state of the British. In 1856, the British Governor General Lord Dalhousie annexed Awadh under the Doctrine of Lapse, as Dalhousie decreed that the Nawab, Wajid Ali Shah, was incapable of managing the state. Awadh was then incorporated into Company territory. This wasn’t the only reason for the Uprising of 1857, but it was part of it.

Although there had been earlier conflict in Bengal led by Mangal Pandey, who had been hung in April 1857, the start point of the Uprising is typically dated to 10th May when troops in Meerut, about fifty miles north east of Delhi, mutinied. The following day those troops arrived in Delhi, and after a lot of bloodshed, took the city.

British forces didn’t retake Delhi until late September, when Bahadur Shah Zafar II, the last Mughal Emperor was taken into custody. After a two month show trial at the Red Fort in Delhi starting on 27th January 1858, he was sentenced to exile. Along with his wife and two sons, he was sent first to Allahabad (Prayagraj), then Calcutta (Kolkata), before finally being shipped to Rangoon in British-controlled Burma on 4th December 1858. He died there on 7th November 1862 and was buried in an unmarked grave.

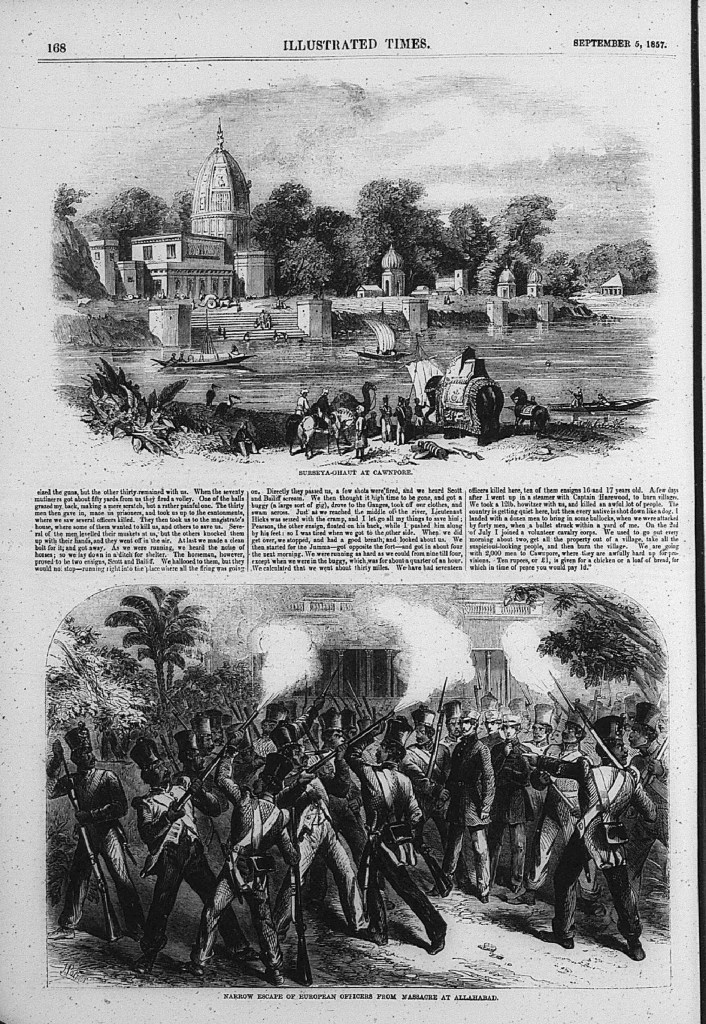

Fighting in Awadh was particularly intense, particularly, but not only, in Lucknow. Events in the city of Cawnpore (Kanpur) where Robert may have been stationed, became a rallying cry, and justification for brutal reprisals by the British.

Satti Chaura Ghat, known as Massacre Ghat, in Kanpur. May 2024

There was no telegraph from the UK to India until 1870, and news of the Uprising took from one to two months to reach London, but the events of the Uprising were widely reported in the British press and debated in the House of Commons. Press coverage tended to stress the violence of the Uprising. So it’s almost certain that Robert would have known what was going on when he signed up.

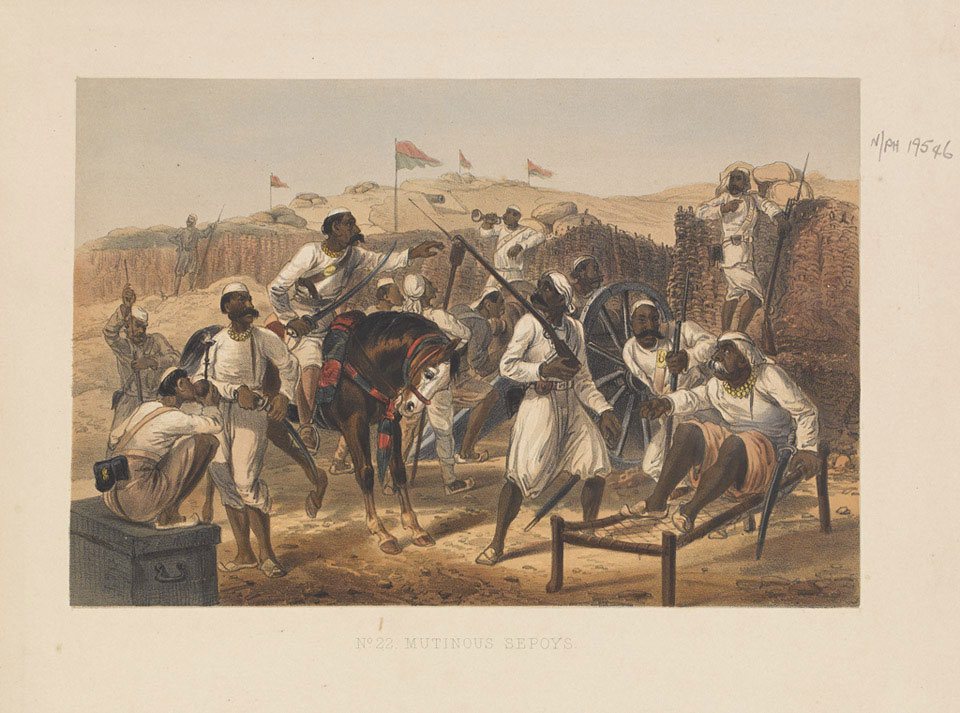

Images of the Indian Uprising from the Illustrated Times, 1857

In all likelihood he would have also known about the related events in China. The trade in tea with China had to be paid for in British silver which, initially, badly depleted Britain’s reserves. In the early 19th century, traded goods from India started to displace silver as a form of payment, and the predominant export was opium. This was incredibly profitable, and silver started to flow out of China to the East India Company and other Indian producers, leaving China facing an economic crisis as well as the social impacts of opium use. China banned the import of opium in 1800, but it was still smuggled in. The conflict came to a head with the First Opium War which ended with the Treaty of Nanking which granted access to several Chinese ports including Canton and Shanghai, and established the British foothold in Hong Kong. During the time of Robert’s childhood, resentment in China at foreign influence grew, and in 1856, with the ‘Arrow incident’, the Second China War started, culminating in the burning of the Summer Palace by British and French forces in 1860, and Chinese surrender in October. The Treaty of Peking, which ushered in the Chinese ‘Century of Humiliation‘, then reinforced foreign influence, and ceded Kowloon, opposite Hong Kong, on the Chinese mainland to the British who would only leave in 1997. Trade in opium to China from British India was the colonial state’s second biggest source of revenue, after land taxes. It peaked in 1879, just as Robert was leaving the army, and only stopped during the First World War.

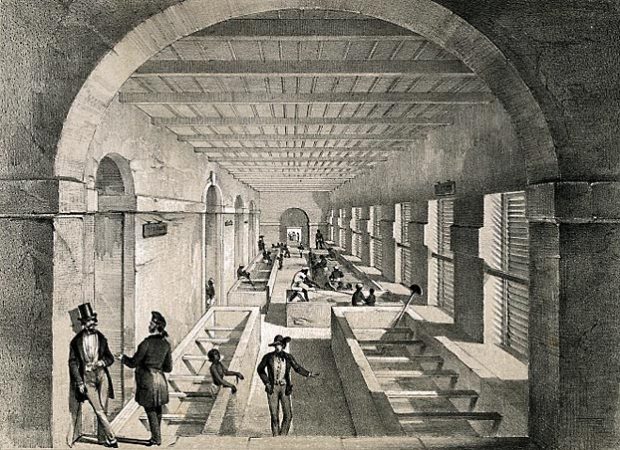

Aside from the tactical difficulties faced by the British in fighting both the Indian Uprising and the Second China War at around the same time, where this fits with Robert’s story is that as he arrived in India through Calcutta, probably in mid-1858, two things would have been travelling in the opposite direction: the last Mughal emperor on a cart, and a lot of opium on boats bound for China.

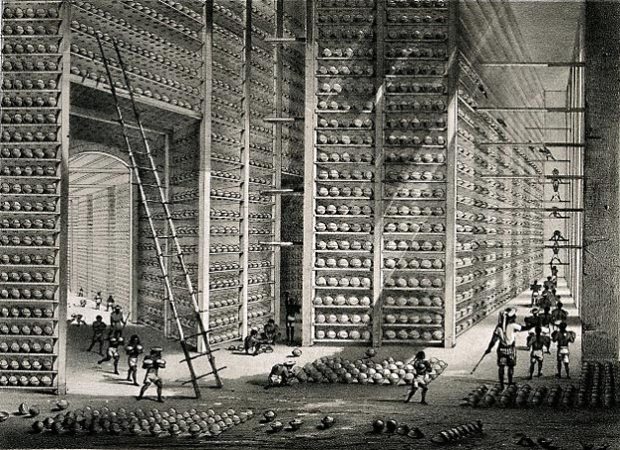

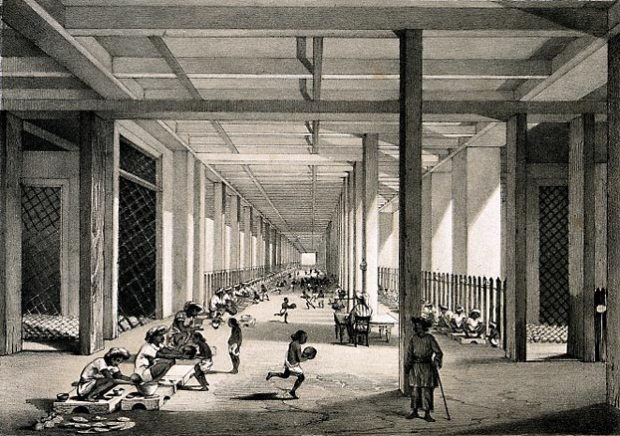

Two sets of graphics produced by eyewitnesses in the 1850s

conveying a sense of the opium production process that was followed throughout most of the 19th century. The first is a suite of lithographs based on drawings by Walter S. Sherwill, a lieutenant colonel who served as a British “boundary commissioner” in Bengal. The second rendering of different stages of opium manufacture consists of 19 paintings on mica by the Indian artist Shiva Lal.

Robert’s time in the army

Robert’s discharge papers, which were issued at the Royal Hospital Chelsea, give quite a lot of information about his time in the army.

He enrolled in the 3rd Royal Surrey Regiment of Militia on 18th July 1854, when he was fifteen, only two years after its formation. Militias had been revived, principally for home defence, at a time of heightened international tension, particularly with Russia in the Crimea. The original 1854 colours of the militia, which Robert must have seen, still hang in the tower of All Saints’ Church, Kingston-upon-Thames.

The church itself is historically significant as the place where Saxon kings, including Æthelstan, the first English king, were crowned.

On 12th March 1858, Robert transferred to the 3rd Battalion of the Rifle Brigade. He was promoted to Corporal in October 1862, but about a year and a half later was demoted to Private for “making a false statement”, for which he was confined for two days. In 1867 he was promoted again to Corporal. He returned to Winchester in the UK on 3rd January 1868, but in July was placed in confinement again, this time for just a day, and was demoted again to Private, the position he held until he was discharged on the grounds that he was found “unfit for service with his regiment abroad” on 12th November 1878.

The record shows that in total he served in the Rifle Brigade for 20 years 245 days, plus the days that he was in confinement. Of this, he spent 9 years and 79 days in East India. His discharge papers don’t say whether his time in India was continuous. However, it seems most likely that it was. The papers show that after 9 years and 298 days he was reengaged by the Rifle Brigade at Winchester on 3rd January 1867, where he served the remainder of his time in the army. It is possible that the discrepancy between the 9 years 79 days service in India, and the 9 years 298 days before he returned to Winchester allowed for one trip back to Britain. This had been the normal practice when travel to India was by sail.

His character record shows that his character had been “very good” and that, in addition to four good conduct medals, he had been awarded the Indian Mutiny medal, and the medal for the North Western Frontier. He had appeared twice in the regimental defaulters book, and had been tried twice by the Regimental Court Marshall. There is no record of wounds or disability, but he was discharged as he was “found unfit for service with his regiment abroad”.

The discharge papers also show that he was 5′ 4 3/4″ tall with blue eyes, although the sign-up record for the militia says he had hazel eyes.

Travel to India

It’s possible to determine roughly when Robert would have arrived in India because he was awarded the Indian Mutiny medal. The awarding of these medals was approved by General Order number 363 on 18th August 1858 and number 733 of 1859 and initially was only to be awarded to troops who served in operations against the “mutineers”. General Order number 771 of 1868 extended the award to anyone who’d borne arms or been under fire, including members of the Indian judiciary and the Indian civil service. The medal was the last campaign medal awarded by the Honorable East India Company, rather than the British Army. The Uprising was all but over by November 1858, although it wasn’t formally declared finished until July 1859.

Indian mutiny medal in the State Museum, Lucknow

In order to get to India in time to be involved in the Uprising, it seems most likely that Robert was shipped to India soon after signing up as it took about eighty days to reach Calcutta from London sailing via the Cape. However, it’s not certain that he took that route. Sailing through the Suez canal would cut journey times by more than half, but it was not opened until 1869, and Britain, particularly in the person of two-time Prime Minister Lord Palmerston opposed its construction up until 1865. However, by 1858 the British were trialling an overland route to India with soldiers sailing to Port Said and then marching across the desert to Suez on the Red Sea, where they would then sail on to India. This was controversial as can be seen from this exchange in Hansard. The logistics of creating the route from Suez to India were also difficult before the opening of the canal. Coal from South Wales had to be transported by sea via the Cape to be stockpiled in Aden, roughly half way on the route to India. To supply Suez, the coal was transported across the desert by camel until a railway opened from Alexandria to Suez in 1858.

It’s also not clear exactly when Robert sailed to India. By the latter part of the 19th Century, there was a “Trooping Season” from September to March during which troops were sent to India in order to avoid the worst of the heat on the journey, but this seems to have come in to place after the route via Suez was opened, besides, the crisis of the Uprising might have overridden any such concerns. Most likely, Robert left England in March or April 1858, sailing via the Cape, arriving in Calcutta in the summer of 1858, where he would have been transported up to Awadh.

This diary by Private Job Shepherd Waterhouse, written in 1864 gives an idea of what transport to India would have been like for someone like Robert.

Time in Awadh

Robert was stationed in Bareilly, now in the Rohilkhand region of the state of Uttar Pradesh. The city is 157 miles north of Lucknow, and 155 miles east of New Delhi. It is also about 750 miles from Calcutta, where Robert would have arrived in India. The city now has a population of nearly a million, and in Roberts time was about 111 thousand.

Bareilly was heavily involved in the Indian Uprising. News of the Uprising reached the city on 14th May 1857. On May 31st, British officials, including the principal of Bareilly college were killed. Khan Bahadur Khan Rohilla declared himself Nawab of the city.

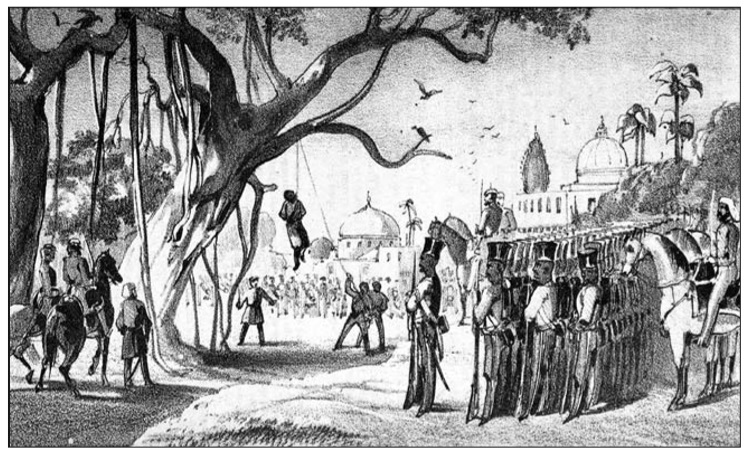

The British wouldn’t regain control until 6th May 1858 when Robert was probably still on his way to India, or had just arrived. Khan Bahadur Khan Rohilla initially escaped to the nearby forests of Nepal with some of his troops, but was caught by the pro-British Nepali ruler Jung Bahadur and was returned to the British, after which he was tried, found guilty and was hung along with 257 others from a Banyan tree at the old office building of the British Commissioner in Bareilly on 25th March 1860. There is now a memorial pillar for the dead at the site, built in 2006.

By the time that the hangings took place, Robert would almost certainly have been in Bareilly, and so may have seen them. These mass hangings from trees were a common practice by the British, designed to punish and to terrorise the local population.

Troops were based in a cantonment district which included a fort, south of the city, which had been built in 1811. The area was badly damaged during the Uprising; this must still have been apparent when Robert arrived. By comparison, the damage inflicted on the Residency buildings in Lucknow at the same time is still very obvious today.

Damage to the buildings of the Lucknow Residency from the time of the Uprising, still apparent in 2024.

The cantonment at that time was mainly divided into three parts: the Indian Infantry lines were in the eastern part, British Infantry lines, such as the Rifle Brigade, and an Indian battalion were in the middle part, while the Artillery lines were stationed in the western part of the cantonment.

Some buildings from the era in the cantonment area are still in place, which Robert would probably have seen, including St Stephen’s church. Captain Hume an executive engineer, laid the foundation stone of the church on 7th January 1861 and the army chaplain, Rev. WG Cowie, conducted the first service on Christmas Day 1862. The church could accommodate about a thousand people. The railway didn’t reach to Bareilly until 1873, after Robert had returned to Britain.

We can’t know how much of Bareilly Robert saw, but it was an important town, with interesting architecture. This is a watercolour painted in 1814-15 of the mausoleum of Rohilla chief, Hafiz Rahmat Khan the father of Khan Bahadur Rohilla, the leader hung by the British. He too had died fighting the British in 1774.

Time in the North Western Frontier

Robert’s discharge papers show that he was awarded the North West Frontier medal. This medal was the Indian General Service Medal, with a North West Frontier clasp. The Rifle Brigade were involved in only one campaign for which this was awarded, the repulse of an attack by Sultan Muhammad Khan on the fort of Shabqadar around Christmas of 1863, and so Robert must have been involved in this campaign.

India General Service Medal (1854-1895), with bar for North West Frontier

Shabqadar is in what was, until recently, Pakistan’s North West Frontier Province, now called Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. It’s location, about fifteen miles north of Peshawar is in what has been a highly sensitive area for millennia as it’s close to one of only two usable land routes for anyone wanting to invade India by land from the west, the Khyber Pass, the alternative being the Bolan Pass much further south. Shabqadar fort lies about forty miles east of the Khyber Pass which is the route to Jalalabad and then on to Kabul.

Shabqadar is about 650 miles west of Bareilly. We don’t know how he travelled there, but the most likely route would have been along the Grand Trunk Road which connected, and still connects, Calcutta in the east with Kabul. Bareilly where he was stationed is near to the Road, and Peshawar, close to Shabqadar, is on it.

In 1900 Rudyard Kipling painted a romantic view of the Grand Trunk Road, both in his letters and the novel Kim in which he wrote “Look! Look again! and chumars, bankers and tinkers, barbers and bunnias, pilgrims – and potters – all the world going and coming. It is to me as a river from which I am withdrawn like a log after a flood. And truly the Grand Trunk Road is a wonderful spectacle. It runs straight, bearing without crowding India’s traffic for fifteen hundred miles – such a river of life as nowhere else exists in the world.” The reality in Robert’s time would have been rather different.

As he passed along the road, evidence of the violence of the Uprising would have been apparent, particularly in Delhi. After its recapture in September 1857 the reprisals by the British had been brutal. Looting, mass hanging and rapes were carried out, driving out much of the population and devastating the buildings of the city of Shah Jahan. Eighty percent of the Red Fort was demolished, and the British established barracks that are still there today. In 1859 the Delhi Gazette recorded that ‘a good deal of blowing up’ was still going in in the Palace. Complete destruction of the city had supporters in India, but also in London, such as Lord Palmerston who wrote that it should be deleted from the map. This was eventually stopped, with the support of, amongst others, Disraeli. However, house clearance was continuing as late as 1863, when Robert would have been on his way through the city on the way to Shabqadar.

It was not just the physical infrastructure of the city that Robert may have witnessed. In 1862, the year before Robert would have passed through, the poet Ghalib wrote of of the city “It is a camp… The female [Muslim] descendants, if old, are bawds, if young, are prostitutes…” These women had been driven to prostitution as a result of the mass rapes committed by the British. British officers had done little to stop this, believing a rumour that British women had been assaulted during the Uprising; a subsequent British inquiry exonerated the rebels from all such charges.

An Italian photographer, Felice Beato, recorded pictures of Delhi and the area shortly after the Uprising which give a feel for what Robert may have seen.

For the British, their major concerns on the North West Frontier were both about raids from groups in the mountains and Russian expansion into central Asia, with the fear that this would then lead on to invasion of India via this route. The Cold War-like conflict between the two powers was termed the “Great Game” by the British and the “Game of Shadows” by the Russians. Ultimately Afghanistan would, in effect, become a buffer state after the Third Afghan War 1919, but at this stage the vulnerability of India in this area was an important concern. Britain had been badly defeated in the First Afghan War 1839-42 only sixteen years before Robert signed up, and would fight the Second Afghan War 1878-80, around the time that he was discharged.

Shabqadar fort was originally called Shankar Garh, it was renamed after its capture by the British when they annexed the area in 1849 after the Second Anglo-Sikh war. The fort had been built in 1837 by Maharaja Ranjit Singh “Sher-e-Panjab” the Lion of the Punjab, who had established a strong Sikh kingdom in the Punjab in the early 19th Century. The fort would help control the Mohmand area, and was rebuilt by the British in 1851. The fort is still in operation today, operating as a training centre for the Frontier Constabulary.

The fort saw fighting many times, but the incident Robert was involved in was around Christmas 1863 when it was attacked by Sultan Muhammad Khan, according to some histories of the North West Frontier medal. However, it’s not clear which Sultan Mohammad Khan this is. Sultan Mohammad Khan, brother of Dost Mohammad Khan died in 1861 and was based in Kandahar, five hundred miles from Shabqadr. Nonetheless, fighting did happen, as can be seen from this account of a Gurkha unit: “On 2 January 1864 the newly-named 2nd Goorkhas were ordered to join the Field Force at Shabqadar, as about 6000 Mohmands and other tribes had moved down from the surrounding hills to take up a position opposite Shabqadar Fort. The Field Force engaged the enemy by artillery and then, led by forward companies of the 2nd Goorkhas and the Rifle Brigade, the Force attacked the enemy who broke and fled.”

Return to the UK and discharge

In 1868, Robert married Sarah Martha Lovell in Winchester.

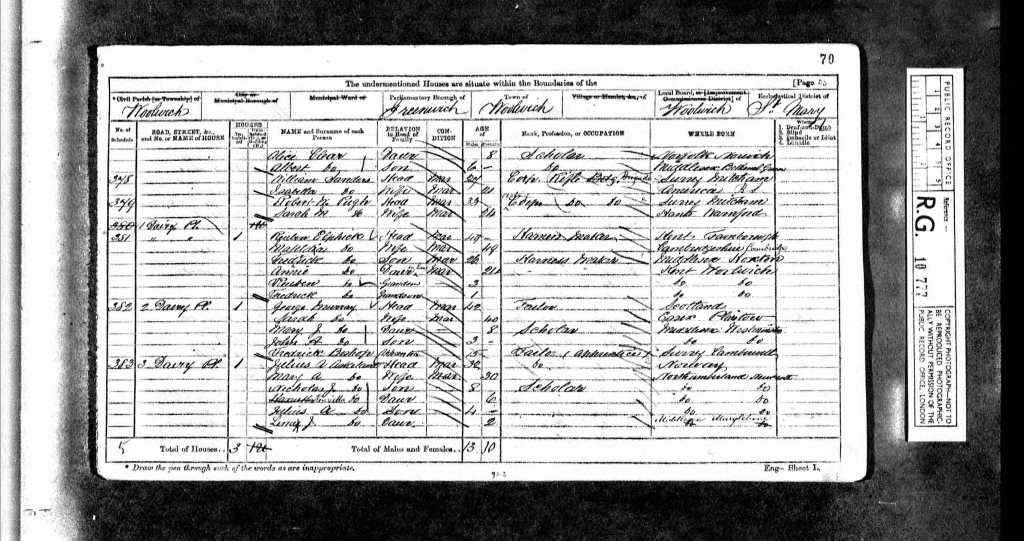

By the time of the 1871 census Robert and Sarah were living in Woolwich at 379 Dairy Place, he was still employed as a Corporal in the Rifle Brigade. Dairy Place doesn’t seem to exist any more, but there is a Dairy Lane very close to the Barracks, most of which has been demolished. This site gives some history of the barracks. However, these pictures, one a postcard from about 1900, and an aerial picture from 1924 show what the area, or at least the barracks, might have looked like then.

- epw010750 ENGLAND (1924). Cambridge and Red Barracks and the River Thames, Woolwich, from the south, 1924.

- Postcard of Cambridge Barracks in Woolwich, ca 1900(?). Photographed at an exhibition in Greenwich Heritage Centre in Woolwich, southeast London, UK.

His discharge papers show that he left the army on 26th November 1878. By the time of the next census in 1881 he was working as a general labourer, and Sarah was a laundress. They had moved to Weeke in Hampshire, and were living at 45 Week Road with a lot of other people. Firstly their two children, William Arthur Augustus who was aged nine and had been born in Woolwich, and four year old Annie Elizabeth who had been born in Sandgate, Kent. Sandgate was and is the site of Shorncliffe Army Barracks. Along with their family, the house was shared with a needleworker called Sarah Payne, and Thomas Farrell, a general labourer like Robert, who was from Waterford in Ireland with his wife Elizabeth and their three young children.

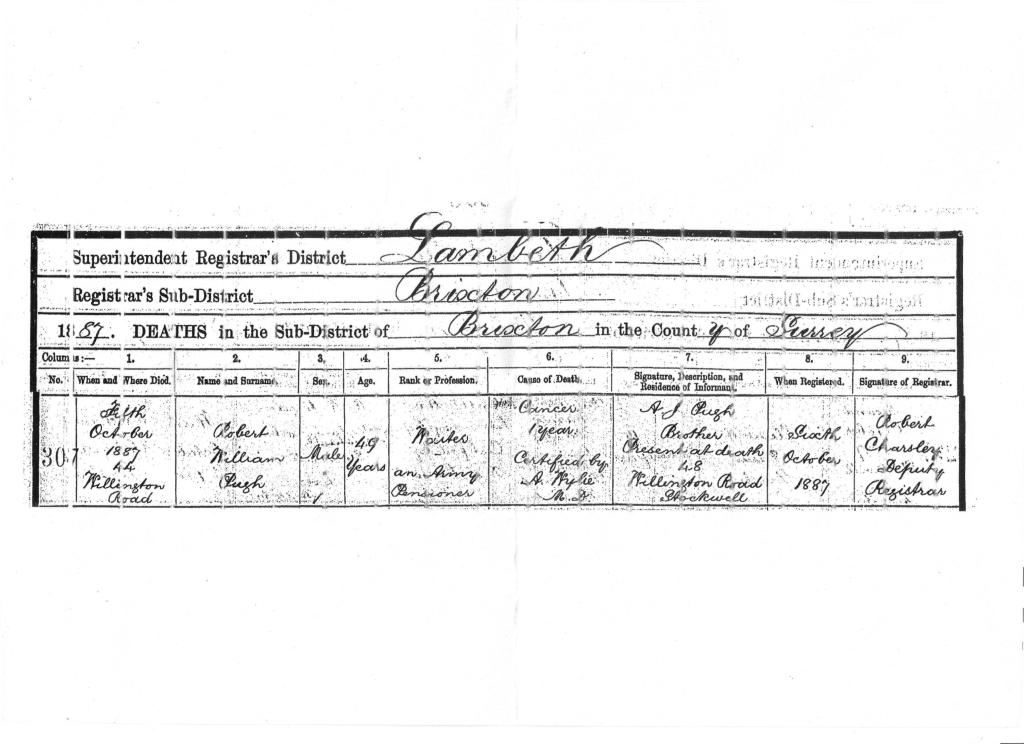

In the last quarter of 1887, Robert’s death was registered in Lambeth. He was aged 49.

His death certificate shows that he died on 5th October 1887. The cause of death was cancer, which he seems to have suffered from for a year. When he died, Robert was living at 44 Willington Road in Lambeth, and the informant on the death certificate was his younger brother, Arthur James Pugh (1848-1921), who was living at number 48 on the same road. After all of his travelling, Robert died about five miles from where he was born. He was buried in Lambeth Cemetery on 10th October 1887, only two miles from the church where he was baptised.

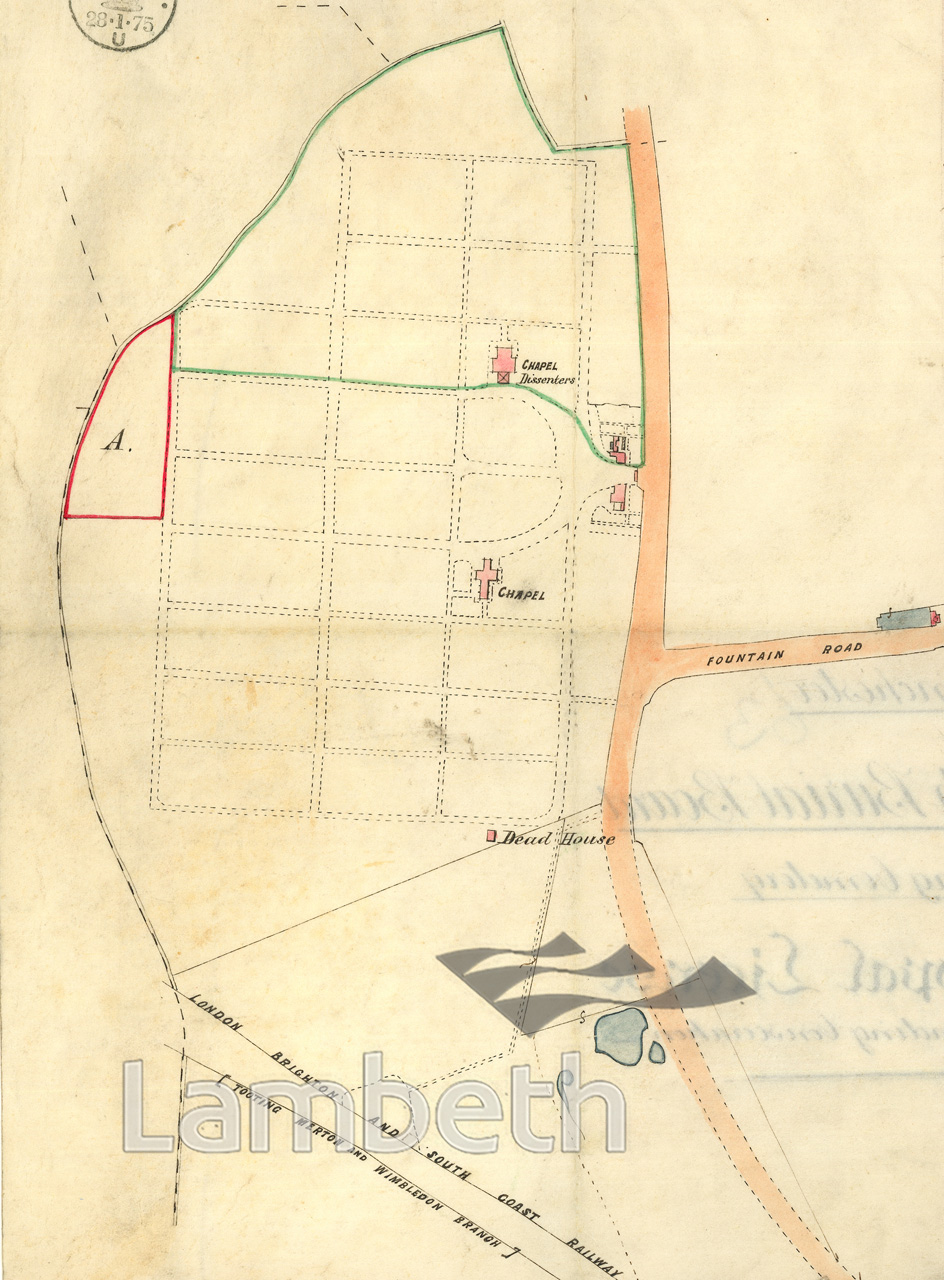

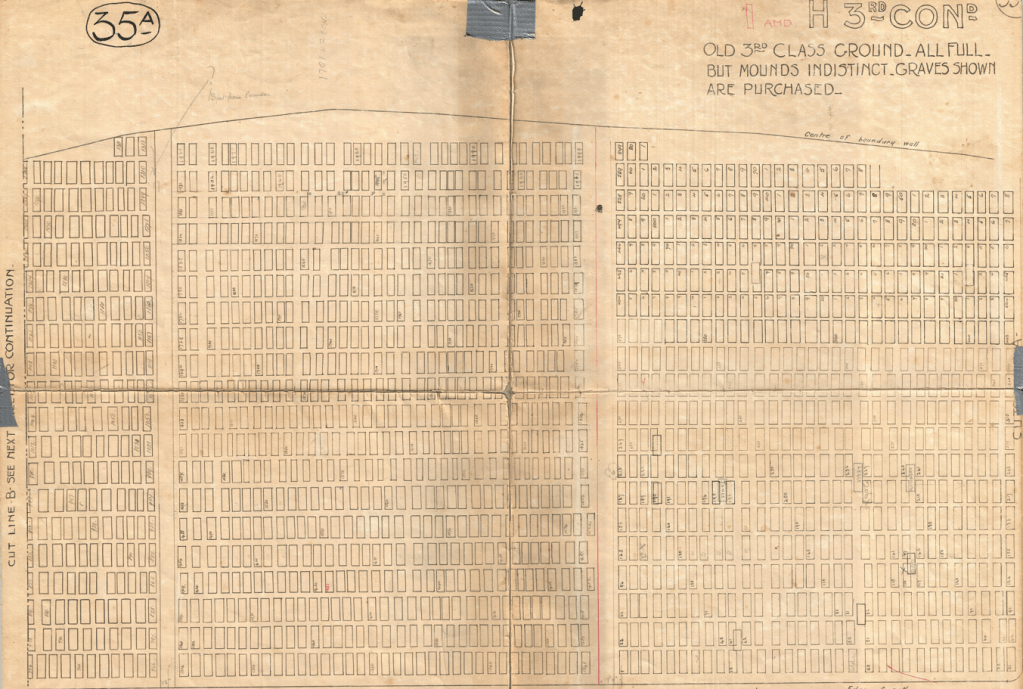

The layout of the graveyard is unchanged since Robert’s time. The first image is from 1875, signed by Edward Harold Browne, Bishop of Winchester. The second is from November 2025 at the Cemetery entrance.

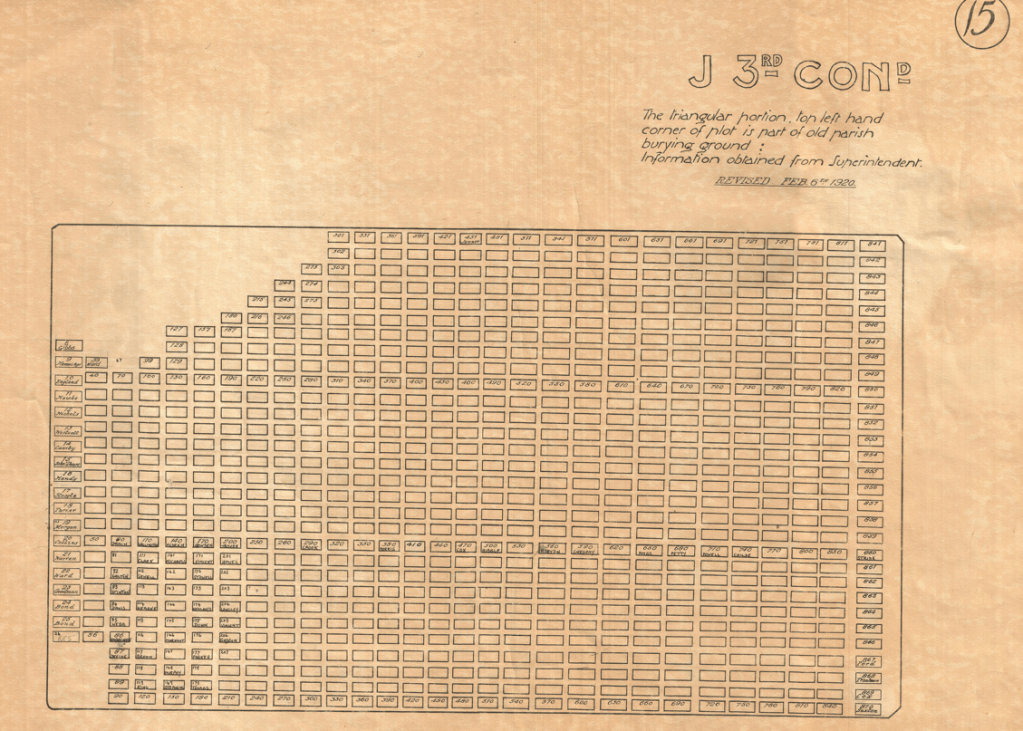

Robert’s grave reference is J3/659, which places him in this area of the graveyard. The exact spot hasn’t been found yet, but is indicated on the plan shown below, and is approximately at the front of this photograph.

Looking at his census records, it seems as though Arthur James moved around the area. In 1881 he had been living at 6-8 Cottage Grove, which is just round the corner from Willington Road, and by 1891 he was living at 38 Willington Road where he still lived in 1901. By 1911 he was living at number 46. He died in 1921, before the next census, and his death was registered at Chesterton, part of Cambridge.

What happened next, and some things about Willington Road

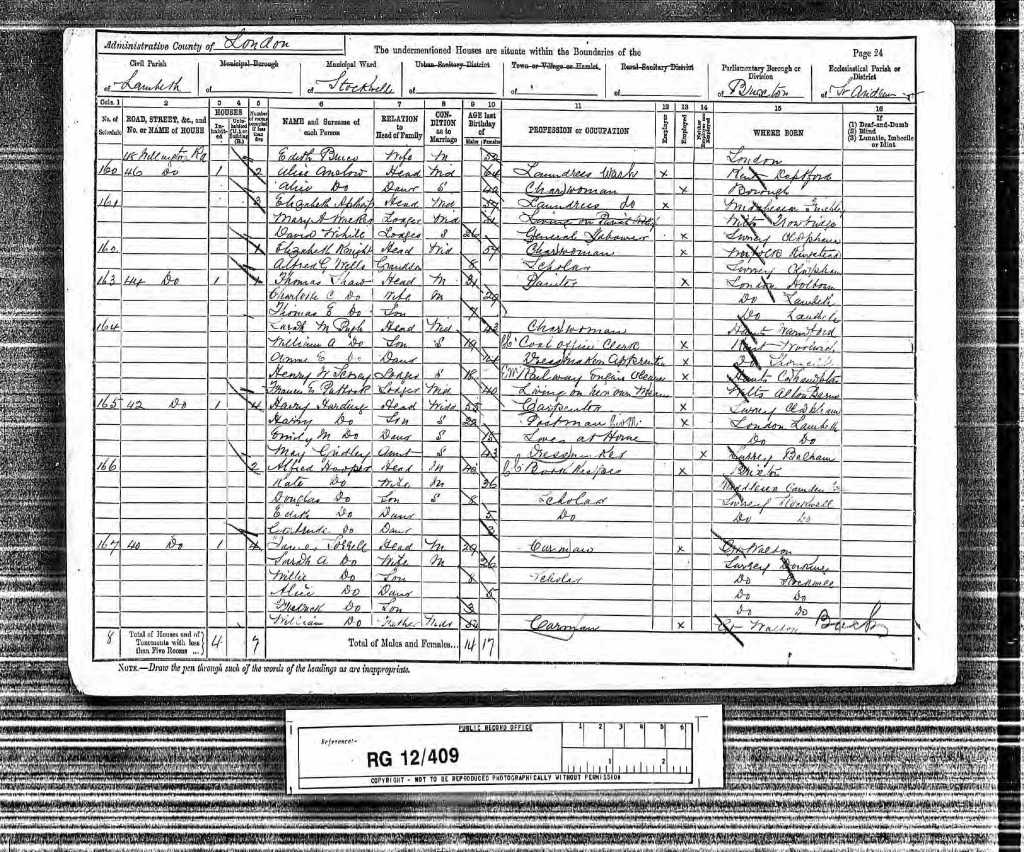

By the time of the 1891 census, Sarah was a widow living in Lambeth at 44 Willington Road, the place where Robert had died, working as a charwoman. By then her son William was working as a coal office clerk, and her daughter Annie was a dressmaker’s apprentice. They shared the house with a family of three, and two lodgers.

The street is still there, but the houses from the period are gone. But there is information available about what the street was like. Firstly, we know that it was built in the mid 19th Century, as London was expanding, because it doesn’t appear on this 1828 map of the area. What would become Willington Road is at bottom left, running down from Bedford Road, which became Landor Road.

By the 1840s, Stockwell Park was being developed, and with the arrival of the London Chatham and Dover Railway in 1862-3 there was a need for housing around Landor Road, which Willington Road runs off. In 1889 Charles Booth mapped poverty in London, colour coding each street. Willington Road just appears on his map (bottom right), being classified as “Fairly comfortable. Good ordinary earnings.” As the map shows, the area was generally well-off.

In 1881, around the time that Robert, Sarah and Arthur were living on the road, the Landor pub was built. It sits at the junction of Landor and Willington Road, as can be seen from this picture taken in 1912, alongside a view of the pub today, which still has some of the original fittings.

Just next to the pub, the 1912 picture shows Avondale Hall. This is now the site of the Central Film School. The building used to house the Italia Conti School of Music, which gave its address as Avondale Hall, and so the building is almost certainly one which Robert, Sarah and Arthur may have visited.

Booth surveyed London again in 1898-99, when Sarah and her brother-in-law Arthur were still alive. As his map shows, the area was still housing people who were “Fairly comfortable”.

This map also shows how close Willington Road was to the South West Fever Hospital, originally built by the Metropolitan Asylums Board as two separate, adjacent hospitals, Stockwell Fever Hospital and Stockwell Smallpox Hospital. The Smallpox Hospital opened on 31 January 1871 to admit patients suffering from the virulent epidemic of smallpox that was then afflicting London, which was part of a wider European outbreak. That year, about 1/10th of deaths in the city were from the disease. As a result of a report of a Royal Commission in 1882, the Metropolitan Asylums Board decided to stop admitting smallpox cases to hospitals within London, apart from very local cases. Other cases were sent to hospitals established in isolated positions on the banks of the Thames or to hospital ships on the river. At the time that Robert, Sarah and Arthur were living there, half of the hospital was given over to smallpox. The buildings were finally demolished in the early 1990s and were replaced with Lambeth Hospital.

The street became a lot more run down in the mid twentieth century, and most of the housing was replaced, but some pictures were taken in 1972 of houses on the road before their demolition, which happened at some time in the mid-seventies. Even in these pictures, it’s clear that the street was once quite well-to-do.

https://www.londonpicturearchive.org.uk/

This last picture of the road from 1975 shows the houses boarded up, ready for demolition.

The 1901 census shows that Sarah and her two children, William Arthur Augustus and Annie Elizabeth had moved to 111 Colebrook Street, St Peter Colebrook, Winchester. Sarah’s profession isn’t shown, but William was working as a grocer’s Clerk, and Annie as a dressmaker.

The house is still there, and looks like this.

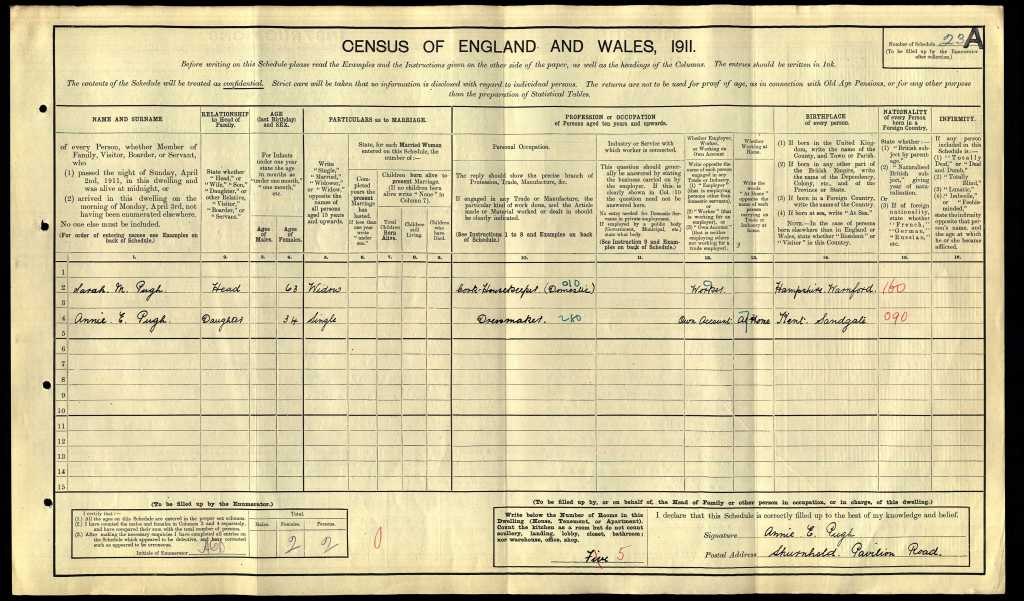

By the time of the 1911 census, Sarah was working as a domestic cook and housekeeper with her daughter Annie, who was a dressmaker, at Shurnhold on Pavillion Road in Worthing.

Sarah died five years later, in the last quarter of 1916, with her death being registered in Lambeth, like Robert.

She was buried in Lambeth Cemetery on 20th November 1916. Her grave reference is H3/437 (see cemetery plan above), which places her in the most overgrown part of the cemetery, shown below. The exact spot has not yet been found, but is indicated on the plan shown below, and is probably at the bottom, just to the right of centre.

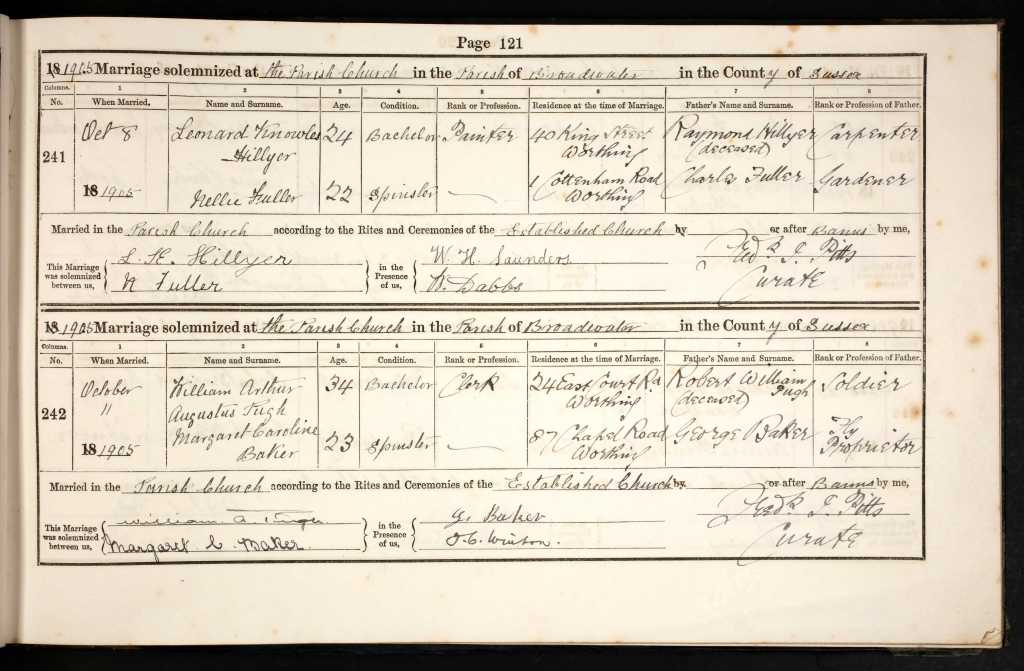

William Arthur Augustus Pugh married Margaret Caroline Baker on 11th October 1905 in Broadwater Church, Worthing.

By the time of the next census, in 1911, William and Caroline had started a family, and were living at Calwich, Northcourt Road, Worthing. William was working as a grocer’s clerk. The youngest of their three children, Margaret Joan Pugh was a month old.

Things to check on

He had no wounds or scars, but what was his illness?

Why Winchester on return?

Check the source for this: There was no telegraph from the UK to India until 1870, and news of the Uprising took from 1 to 2 months to reach London.

Check the source for soldiers being allowed one trip back to Britain in the age of sail.

Did he join the army of the East India Company, or the British Army?

How did he get to India, how did he get back? sail or steam, was it Calcutta rather than Bombay (I think this is a racing certainty but check). How did he get transported to Awadh? Was there a railway yet, and how far or would it have been river or road, i.e. the Great Trunk Route? How long was it to get there (say to Bareilly for sake of argument), in all likelihood the monsoon would have started so this would have been miserable.

Check the 1911 census records for Sarah. The house had 5 rooms, so it seems most likely that she and Annie were working in service there. This might help explain why her death was registered in Lambeth. It seems like she went back to live with Arthur, her brother-in-law, but look into this.

What else did he do in the army? Look at Rifle Brigade history.

Look at Gazette for records of what the Rifle Brigade was doing.